Reflections

Chapter 16 ended our tour of ten separate dimensions in volunteer space. The next two

chapters will attempt a summation with several different approaches. Before that, I would

like to exercise author's license in sharing some reflections which have occurred to me at

this point: general, personal, and mystic.I have

sometimes been accused of being a thinker, and I've not chosen to object to that claim as

decisively as I might have. Valid objections do exist, as readers of this book may have

some cause to confirm. My own view is that a real thinker can deal with a wide range of

issues and problems. Yet, in my whole life I can recall thinking seriously about only two

problems: Why is it that people help one another? And, why is it that people work and

enjoy it?

The questions are stated from the positive side because of

long habit in the volunteer leadership field, for we are the people who prefer the study

of the positive. Other fields may choose to focus on how and why things go wrong:

neurosis, breakdowns in society, and so forth. We are the people who revel in what can go

right - how and why people do good things - and we are the people who believe we can

promote cause for rejoicing in a more humane future. I hope volunteer leadership never

changes in this respect.

Nevertheless, the more complete statement of the two

questions is: Why do people help each other as distinct from hurting one another, or being

indifferent to one another? And, why do people work and enjoy it as distinct from working

and hating it, or working and not caring either way, or not working at all? I happen to

believe they pose fundamental questions for volunteer leadership, perhaps the fundamental

questions. In any case, the basic question - why do people help - has been grappled with

throughout this book; the work enrichment issue has entered secondarily as an important

spin-off.

This book has struggled to develop a strategy whereby we

can facilitate more helping and create a more favorable balance between help versus unhelp

in our society. This strategy is essentially a set of prescriptions for making it easier,

more convenient, and even more pleasant for people to help, by identifying their natural

inclinations more carefully, and relating helping work more closely to these inclinations.

The most explicit statement of this strategy is the oft-repeated exhortation: make the

minimum change in what people want to do and can do, which has the maximum positive impact

on other people. Since we are not sufficiently aware of all the "can do" and

"want to do" styles which may appeal to people - and they may not be fully aware

of these styles either - I have attempted to systematically explore the widest possible

range of helping styles available to people. A huge set of logically possible options in

involvement styles have been found; a few of them have been discussed but most were barely

noted or only indicated in a very general way. This is one of the reasons I call the set

of options "volunteer space." Like space, the full range of options in helping

styles are barely understood today, scarcely mapped, and virtually unvisited.

The Size of Volunteer Space

This book is merely a first foray into volunteer space, enough to assure us that the

volunteer world is round; that is, we won't fall off if we walk beyond the visible

horizon, and it may be well worth the walk. These last two chapters will get us ready for

more ambitious hiking in two ways. The first is an exercise in outward moving logic; the

second is a venture in humanity at home. First, let's check the trail behind us. Ten

dimensions in volunteer space were traveled. Each was anchored by a pole at either end and

usually at least one point intermediate to these extremes. Thus:

as an |

|

as one |

|

With a |

individual |

|

of a pair |

|

group |

We have sampled at least the two polar

positions in volunteer involvement on each of ten dimensions and on some dimensions, we

examined one or more intermediate positions as well. This probably totals about thirty

variations in style of volunteer involvement or locations in volunteer space. We also

briefly visited a few promising combinations between poles of different dimensions; for

example, individual/occasional (skillsbank) and direct/with group (a church tutoring

project). There were, perhaps, another 15 or 20 of these combinations in volunteer space.

In all, we have visited about 50 locations in volunteer space or variations in volunteer

involvement style.

How many are there left to go? Logically, about 60,000! We

have been to less than one-tenth of one percent of all the places there are to see in

volunteer space. This is something like a ten-minute nature hike in Rocky Mountain

National Park. It's illustrative, and you get the idea there is much more worth seeing,

but you haven't really been through the park; you have just been in it, and barely that.

Is volunteer space really that big? Let's run over the

outer boundaries with two extremes on each of the ten tracks.

1. Continuous......................To

....................... Occasional

2. As An Individual ..............To ...................... With a Group

3. Direct..............................To ...................... Indirect

4. Participating Action .........To ...................... Observation

5. Organized Formal Structure... To ................. Informal, Unstructured

6. Via Work....................... To ........................ Via Gift-Giving

7. For Others .................... To ........................ For Self

8. Accept System ............. To ....................... Address System Rules

9. From Inside the System.. To ....................... From Outside the System

10.Losing Money ............... To ...................... Break Even (Plus?)

These poles may combine in any way except with their

opposite; you can't be both a continuous and occasional volunteer at the same time.(1) But

continuous service can be either as an individual or with a group; that is, either pole of

one dimension can combine with either pole of any other dimension. Moreover, most of these

combinations make sense logically. A few do not, on first scan. For example, what is

observational gift-giving or a "break-even" gift, for that matter? Sometimes,

too, there is partial overlap. Observational volunteering tends to be indirect because it

is often in a supportive relation to other work, but not all indirect participation is

observation. Moreover, the participating action and work poles substantially overlap one

another, while many of the other dimensions are variations on the work and action poles.

But generally either pole of any dimension can combine with either pole of any other

dimension to form a potentially meaningful variation in volunteer involvement or location

in volunteer space. For the moment, let's assume this is always so.

Another concern might be that some extreme poles are

completely outside the limits of volunteer space; for example, totally "for

self" is not volunteer at all, nor is more than breaking even on the money dimension.

If this bothers you, simply foreshorten these poles. Thus, I think earlier chapters have

established that there is some degree of acceptable self-interest in volunteering; also

that activities accepted as volunteering can have some significant relationship to money

in exchange for work, even if these activities don't make a profit.

A further point: volunteer participation cannot be

completely described until it is located on all ten dimensions (and probably others as

well). Not to do so would be like trying to visualize a person when the only data you had

on that person was brown eyes; you wouldn't begin to get a reasonably complete picture

until you also knew height, weight, sex, and several other characteristics. Similarly, it

isn't enough to say a person is volunteering continuously, because you still don't know

whether the person is volunteering as an individual or with a group, directly or

indirectly, in service, policy, or advocacy modes, and so on. One example of such a

complete description of volunteer involvement mode would be positions at the leftward pole

of all ten dimensions. Here we would have a volunteer who is participating continuously/as

an individual/directly involved with the problem/through overt action /in an organized

setting/working (not gift-giving)/for others/in a way which accepts the system as it is

(service)/works from inside this system/and pays his or her own expenses. This could be a

volunteer probation officer, but we don't know that for sure, because while mode of

volunteer involvement is quite completely described here, we are still not describing the

substance of the work.

Now in the preceding marathon sentence, change just the

first description of the ten from "continuously" to "occasionally,"

and the ten-word combination describes another distinct mode of volunteer involvement.

This could be a community resource bank volunteer, working for the welfare department. Now

continue the same two sequences with the second dimension at the "with a group"

instead of "individual" pole. Keep going, and you will discover over a thousand

distinct ten-way descriptions of volunteer involvement modes or locations in volunteer

space. To be precise, there are 1024, or 210.

This is unrealistic because it is a drastic

underestimate of all the locations in volunteer space. First of all, there are almost

certainly more than ten meaningful dimensions along which volunteering can vary, but let's

leave that alone for the present. The point is that there are a whole series of

intermediate points between the extremes in each of our ten dimensions. Continuous grades

into occasional; "for others" grades into "for self" by degrees of

self-interest; between "as an individual" and "with a group" there is

a pair and a family, and so on. This book has discussed a number of these realistic

intermediate points. If we added only three or four major points on each of the ten

dimensions, the number of possible combinations or locations in volunteer space could be

vastly increased - many millions of distinct locations. Let's take the most oversimplified

instance in which only one intermediate point exists between extreme poles on each of the

ten dimensions. Thus, instead of just:

As

an

individual |

|

To |

|

With

a

group |

|

|

| It would be something

like: |

As

an

individual |

|

As

one of a pair |

|

With

a

group |

|

|

| Or instead of just: |

Only

work |

|

To |

|

Only

gift-giving |

|

|

| It would be something

like: |

| Only work |

|

Work

and gift-giving

integrated |

|

Only

Gift-giving |

|

|

| And instead of just: |

|

|

|

For

others |

|

TO |

|

For

self |

|

|

| It would be something

like: |

|

|

|

For

others |

|

Some

Self-interest |

|

For

self |

|

|

How big is volunteer space now? There are

59,049 locations, distinct variation in volunteer involvement or 3(10). The number of

combinations of ten possible with four points on each dimension would be 4(10) or slightly

over a million locations in volunteer space (1,048,576) to be exact). But this is a case

for the world’s champion three-dimensional volunteer chess player.

For now, 60,000 locations are quite enough, even in an era

when millions and billions are bandied about casually. Human-sized illustrations are

helpful. A 1974 NICOV study found the director/coordinator’s salary averaging about

$10,000 a year, full-time.; Adjusting that for inflation and, let us hope, progress,

let’s say the average is $12,000 per year today (still low). Sixty thousand as

dollars represents every single dollar paid to five full-time directors of volunteers over

a one-year period, or, if you like, every single dollar of a volunteer director’s

salary for five years.

As indicated earlier, some of these sixty thousand

variations in volunteer involvement will prove meaningless logically, practically, or

both. I would guess half or more of them will prove potentially meaningful after study; in

any case, many thousands of them must be. But we won’t know for sure until we scan

them all. Any location unvisited may be a beautiful place we will be sorry to have missed.

In summary, and with rather ridiculous precision:

Volunteer space

has |

59,049 |

|

locations |

We have visited

about |

50 |

|

locations |

|

|

|

|

There are |

58,9999 |

|

Left to go |

Even if there are only ten thousand

potentially meaningful locations left to visit, it is too easy to get lost out there,

especially if one of us goes out alone. Eventually, I would see this organized as a

collective enterprise for volunteer leadership. We certainly wander aimlessly without a

systematic search plan.

Systematically Exploring Smaller Sectors of

Volunteer Space

There are reasonably easy ways of tracking through smaller sectors of volunteer space.

Suppose we want to exhaust combination possibilities in simplified versions of only three

dimensions (simplified because we eliminate intermediate points between two poles). Let's

do this for three fairly well-understood dimensions:

CONTINUOUS |

|

OCCASIONAL |

|

AS

AN INDIVIDUAL |

|

WITH A GROUP |

|

ACTION

((DOING) |

|

OBSERVATION |

|

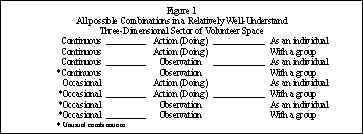

All possible combinations

would look like Figure 1.

We obviously are still pretty close to camp in volunteer

park; that is, in Figure I we are generally looking at reasonably well-identified modes of

volunteer involvement. Thus, the continuous action volunteer who operates as an individual

could be the candy striper, the volunteer counselor, the volunteer who has a regular show

on public radio. Still, even in this fairly well-understood region of volunteer space, the

asterisked combinations in Figure I are at least thought-provoking.

Continuous observing with a group (birdwatchers?) makes one

wonder whether there are certain kinds of helpful observation which can be done better

with a group or as a pair than as an individual. This could add accuracy and provide more

mutual support among the watchers, hence be an attractive mode of involvement for them.

Occasional observing as an individual suggests that maybe

there are helpful possibilities for involving watchers on a less-regular, less-organized

basis - simply watching wherever they happen to be. Occasional observing with a group

suggests similar possibilities. Maybe some people are willing to be involved as

time-limited occasional watchers, when they wouldn't sign on for more time-extended

observational chores (an observational skillsbank?).

Occasional action with a group brings to mind the

traditional volunteer-sponsored Christmas party for kids, or other annual projects. But it

also makes me wonder if there isn't such a thing as a skillsbank or human resource bank

composed of groups, awaiting more self-conscious development on our part.

In sum, Figure I exhausts all eight possibilities for

bipolar combinations in one sector of three-dimensional volunteer space. All eight

possibilities are reasonably meaningful, and four of the eight suggest intriguing further

development of volunteer styles for attracting more people to help-intending work. That is

a pretty good batting average thus far, especially considering that the three dimensions

involved are supposed to be relatively well-mapped parts of volunteer space.

One more illustrative exploration occurs in a section of

volunteer park a little further away from home base. This involves three dimensions which

are perhaps less fully identified in our self-awareness of volunteering.

|

|

From Outside Avocacy) |

|

|

|

|

System-Accepting |

|

System Addressing |

(Service) |

|

|

|

|

|

From Inside

(Policy) |

Work |

|

Gift-Giving |

|

|

|

Organzied |

|

Informal |

To simplify, we will discuss the "from

outside" variation on the system-addressing pole; that is, advocacy or issue-oriented

volunteering. Figure 2 describes all possible combinations in this sector of volunteer

space. As in Figure 1, unusual combinations are asterisked.

Organized service or advocacy work are well enough

understood as volunteer involvement styles. Moreover, Chapter 12 should have helped us see

that the same kind of help-intending efforts can occur on an informal basis. But what are

"service gifts," either organized or informal? 'Me phrase may be little more

than a redundancy; gifts are by definition help-intending (Chapter 13), which is to say

they are meant to be of service to their recipients. There is nevertheless a useful

reminder here: things as well as effort can be a medium for the expression of caring.

Furthermore, gifts and work are not only alternative modes of helping; the two can be

effectively integrated in a total caring package, and we could more deliberately exploit

these integrative possibilities (see Chapter 13). An intermediate point on the work--gift

dimension would be a better representation of this possibility: organized service giftwork

(integrated) and informal service giftwork (integrated).

Finally, in our lexicon, "service gifts"

literally means materials or money donated within a system-accepting framework; that is,

the gifts are given in a manner which is consistent with the status quo, or actually

reinforces an existing system of rules. Donations to an established charitable cause would

then meet the test of being service gifts.

But not all gifts need to be engaged in a status

quo-accepting manner, and this brings us to the other two intriguing descriptions in

Figure 2: organized advocacy gifts and informal advocacy gifts. Once again, let's assume

that the difference between organized and informal isn't critical for our present

discussion.

What are "organized advocacy gifts"? Is this a

case for the constable, that is, bribery? Could be, as in the case of a calculated gift to

a dishonest politician. But a little more thought conjures up positive forms of advocacy

giving. Suppose you are a volunteer companion working with a little girl. You sense she

has a special flair for understanding spatial relationships (engineering, architecture,

interior decoration). You want to encourage (persuade, advocate) exploration and

development of this potential by the little girl. So you give her a few dollars worth of

appropriate materials to work with: drawing paper, marking pens, a ruler, and other tools,

You don't expect any "favors" in return, except the satisfaction of successfully

persuading the girl to explore, release, and refine her potential. Your advocacy gifts are

an inextricable part of your advocacy efforts. In all, this is a most benign bribery, if

it is bribery at all.

Gifts can also be relatively expensive and still be part of

positive persuasion (versus malicious calculation). Suppose you have a friend with a

serious hearing problem. A hearing aid would probably help her function far better in the

world of sound - this much is known through medical/audiological testing. But your friend

is very sensitive about wearing a hearing aid; you and several other concerned

acquaintances have been unsuccessful in efforts (work) to persuade her to try a hearing

aid (advocacy). One of the arguments she gives against a hearing aid (counter-advocacy) is

the expense, with no absolute certainty the hearing aid would help (some people can't get

accustomed to wearing a hearing aid). You suspect the above argument is largely a

rationalization for your friend's emotional sensitivity, and you say so. She remains

unmoved, and your advocacy work is at a dead @nd. So you and a few other concerned

acquaintances find a reputable hearing aid dealer and purchase a gift certificate which

will cover the cost of a good hearing aid, and is refundable after a trial period if the

hearing aid doesn't work for your deaf friend. The gift certificate is given to your

friend, perhaps anonymously.

Your advocacy work alone did not succeed. This

"advocacy gift" alone might well have failed. But the advocacy work-plus-gift

might succeed. (It might fail, too, but I have seen something like it succeed, and what

have you to lose, if you really care about your friend?)

The second three-dimensional sector of volunteer space

(Figure 2) is less well-understood than the first (Figure 1). The interpretations are

correspondingly more difficult, and even somewhat labored, for the four unusual listings

in Figure 2. Indeed, I am not sure how much stimulus value these interpretations would

have for people who had not already read this book and agreed with at least some of its

conclusions.

Developing Your Own Definitions of Volunteer Space

The difficult interpretation case leads us to a second main purpose of this chapter. The

first main purpose, you recall, was the need for a systematic way of exploring all the

locations in volunteer space. The additional point now is that you shouldn't be forced to

define these locations in the same way I do. In our volunteer park analogy, what I see as

a good campsite on our hike through volunteer park may not be the same as what you see as

the best campsite. Specifically, throughout this book, I've asked you to go along with my

descriptions, titles, and interpretations of the ten dimensions covered. Thank you, but

you're on your own now, as much as you wish to be. You are absolutely free to do any of

the following:

1. You can modify descriptive terms to suit yourself, at

either pole or any intermediate point in any of the ten dimensions.

2. You can "shorten" any dimension so that the

pole on the right makes more sense to you. Thus, if "for self" goes too far for

you as compared to "for others," substitute something more intermediate, like

"self-interested." Similarly if pure gift-giving gets too confusing when

contrasted with work, use something like "work-plus gift-giving" for your right

pole.

3. You can also work with combinations of intermediate

points as well as poles, simply because these intermediate points seem interesting to you.

For example, between "as an individual" and "with a group," "a

pair" might seem a significant combining option to you; and between "for

others" and "for self," the "mutual helping" alternative might

promise a yield of significant combinations with other descriptors.

4. You can completely discard any dimension.

5. You can add any new dimensions you want to.

Though I'm locked into the descriptors chosen for this

book, I wish you well in developing your own perceptions of volunteer space. And please

note: the systematic exploration process, described in this chapter will apply, whatever

descriptors you choose for poles and intermediate points in your perception of volunteer

space.

The exploration process thus far is simple enough for

exploring any three-dimensional sector of volunteer space. Look at Figures 1 and 2. One

dimension rotates vertically from four left pole titles followed by four right pole titles

down the first Column; the second dimension is left pole titles followed by two right pole

titles down the second column-, while the third column is a simple alternation between

left and right pole titles. For combinations of four dimensions, you would add a fourth

column in which you repeated one polar title eight times running, then the other polar

title eight times running. Suppose you wanted to graft Direct-Indirect onto the three

dimensions in Figure 2. You simply write "Direct" eight times in a new column of

Figure 2, then repeat the entire figure with "Indirect" in that column. You

could also do it by taking 2 single card with "Direct" written on it, and

another card with "Indirect" on it, running each down Figure 2.

A Process for Systematically Exploring Wider

Regions of Volunteer Space

Exhausting all possible or promising three-way and four--way combinations should keep you

busy for a while. Using the above manual method for sectors in volunteer space of five or

more dimensions is going to give you writer's cramp, and maybe cerebral cramps as well.

We'll need some help in these higher-level combinations of dimensions. In terms of our

anaology of hiking through volunteer park, we've gone about as far as we can go without a

horse. The horse is our friendly computer. The property programmed computer scarcely

blinks before commencing to print out all 1,024 locations in bipolar volunteer space or

all 59,049 locations in three-point volunteer space.

I worked with computers long ago and still suffer anxiety

attacks. Among other things, I grew up before the computer age. But I have been fortunate

in a professional association with Steve Hansen, VOLUNTEER's information specialist, who

also happens to be a computer programmer. He therefore understands the human side of

volunteering, along with computers; and he provided the basic ingredients for this

chapter: software, hardware, and concepts. In a short paper available upon request from

VOLUNTEER, Steve explains and presents a computer program which will print out all ten-way

combinations possible among all poles of each of the ten dimensions (the only restriction

being that a pole of any dimension cannot combine with its own opposite pole). Steve has

actually run this program, and we have a printout of all 1,024 combinations. However, if

you prefer to use your own titles for the poles of the ten dimensions, Steve's paper

indicates how you can run your own computer program, or have someone run it for you. Steve

Hansen advises that the ten-dimensional program was run on the University of Colorado's

Control Data Corporation 6400 computer, costing a total of $1.89. The computer allowed

itself to be bothered for all of ten seconds with this exercise. The largest fraction of

the cost, by far, was in printing the 1,024 locations - $1.29. The size, speed, cost per

unit time, and other characteristics of individual computers all effect the price, and the

fact that they differ widely with different machines make it impossible to make a firm

prediction that it would always run this cheaply, but it seems safe to say that a total

cost of over ten dollars for this program would be very rare.

Steve's paper also describes a more ambitious computer

program in which there are three positions on each of the ten dimensions: two poles and

one intermediate point. This program yields 59,049 combinations for describing volunteer

involvement styles.(2)

For the foreseeable future, 1,024 combinations (bipolar) is

quite enough. The printout is 17 tightly packed pages (no paragraphs or illustrations) and

reads something like the telephone directory - at least there is some of the interest of

the yellow pages with a subject heading for shoppers entitled "Volunteer Involvement

Styles" (comes right between "Voice Recording Service" and "Wake-Up

Call Service").

Whoever has persevered through this book thus far deserves

a sample of what these ten-adjective involvement style descriptions look like. You will

also have earned the right to a sample considerably smaller than 1,024. The introduction

to this chapter listed the very first ten-adjective description in the printout:

continuous, individual, direct, action ... etc. involvement. The comment on that style

description was that it was easily recognizable in our current awareness of what

volunteering is; that is, a volunteer probation officer, or a candy striper, has that

style of involvement. The reason this style was so recognizable is that the descriptors

were all on the left or more traditional poles of the ten dimensions. Whatever left poles

tend to predominate in the printout, a similar sense of recognition occurs: "Yes,

I've seen that kind of volunteering before."

On the other hand the listing begins to look strange

whenever certain radical (as volunteer) poles appear, such as "for self' or

"gift-giving," and at that point, one is well advised to substitute less extreme

phrases, such as "self-interested" and "gifts integrated with work."

There are certainly some wild descriptions, such as, continuous/as

individual/direct/observing/organized/gift-giving/for self/system-addressing/from

outside/break-even. This might be a person engaged in an ongoing organized attempt to

bribe himself or herself to look at the rules he or she lives by. Moreover, the advocacy

somehow manages to be within a single person, from outside the system, and is on a

break-even basis (who pays for the gift?). Still, if you changed just two phrases -

"for self" to "for others," and "observing" to

"action" - the involvement style might begin to make sense; we have discussed

something like it previously in this chapter in the example of the child with potential

for architecture, engineering, etc.

Almost all the descriptions make one think hard, and the

effort pays off with a glimmer, at least, in some cases. Take: continuous/with a

group/indirect/observing/informal/ work/for others/system-addressing/from

inside/break-even. This could be a kind of informally constituted Board or study committee

(system-addressing, from the inside) looking at how to improve the rules of a larger group

of which they are members. If formal Boards are composed of volunteers, then so are

informal Board-like groups (Board-like because these policy-type volunteers are operating

continuously, not just a meeting every few months). I'm sure others have thought about

this kind of volunteer style, but probably under another name.

Now let's look at: occasional/as

individual/direct/observing/organized/work/for others/system-addressing/from

outside/break-even. This could be a stipended ombudsperson, on call from a human resource

bank!

Now let's take:

continuous/individual/indirect/observing/organized/gift-giving/for

others/system-accepting/from inside/money-losing. At first glance, this looks palpably

absurd; it doesn't seem that observing and gift-giving could go together-, and I'll admit

any reasonable interpretation calls for a resolute imagination. But what about a volunteer

comparison shopper? Someone else buys the materials, or at any rate, this is not the most

important part of the volunteer's task. Rather, the comparison shopper volunteer's service

(for which he or she pays expenses incident to the service) is in selecting the most

appropriate materials, and in getting the best possible deal on them.

Only 1,019 ten-way descriptions left to go. I leave that

task to hardier souls. Indeed, it may be that computer-assisted search of volunteer space

is more for the student than the practitioner, more for serious research than day-to-day

application. In the first place, not everyone will have access to a computer for

enumerating anywhere from about 1,000 to 60,000 or more ten-word descriptions of volunteer

involvement styles. Even if you do get such a printout, what practitioner has the time or

endurance even to look at each of the descriptions? Finally, even if you do have the time

and endurance, the previous section has indicated that interpretation of many of the

ten-word descriptions requires considerable mental agility. In the first place, it's

extraordinarily difficult to juggle ten ideas at one time, and make coherent sense of the

entire collection. (I believe psychologists say that most of us can hold no more than four

or five things in our minds at one time.) What seems to happen is that as the collection

of descriptors gm larger, you are more and more likely to get one that seriously violates

the sense made by the other descriptions in this collection. Therefore, though ten-way

descriptions are logically the most complete and probably the most appropriate for

research on volunteer space, I think combinations of between three and six adjectives are

probably more useful for everyday purposes of reminder and discovery in volunteer space.

Exploration as a Learning Game

An earlier section of this chapter illustrated a systematic process for exploring three-

and four-dimensional sectors of volunteer space. That method is systematic and feasible;

it may also get a bit boring, partly because it lacks some of the elements of surprise.

Therefore, I'm going to illustrate a somewhat less systematic way to meander through

volunteer park, if that's your style. You can make something of a game of the exploration.

Here are the outlines of one simple game of this type; let's call it "three-card

style." 'Me game would be played with cards, each of which has the title of a pole of

a dimension; thus:

| Continious |

and |

Occassional |

| ---------- |

|

= = = = = = |

As

Individual |

and |

With

Group |

O |

|

Ö |

And so on.

If you choose to use both poles of all ten dimensions,

there will be twenty cards in all. There are 18 cards if you choose to use only nine of

the ten dimensions, 16 cards if you want to play with only eight dimensions, etc. You can

use your own polar titles and dimensions and you can also use cards marking a midpoint

between, but to keep it simple for purposes of illustration, let's say we have 20 pole

cards. Make duplicates of these 20 cards, so you have two "continuous" cards,

two "occasional" cards, or a total of 40 cards.

Now add two wild cards:

You can use these wild cards to represent

either pole of any dimension. Or in some versions of the game, a wild card permits

creation of your own new or modified titles.

Finally, you might prefer to have separate POLICY and

ADVOCACY cards, rather than having these styles be a combination of two cards: system

address-from-inside and system address-from-outside respectively.

Up to five or six people can play.

1. Deal three cards to each person (face down, please).

2. Each player, in turn, has a choice of passing, standing

par, or drawing one card from

the remaining deck on the table. If the player keeps the

card, one card from the hand must be discarded.

4. Two cycles completely going around the table are

mandatory.

5. After the completion of the second cycle, the rotation

continues until (a)'the deck in the center is exhausted; (b) all players participating

have passed in sequence; or (c) a player, having what seems to be a good hand,

"calls", and all players must lay down their hands.

6. What is a good hand? A hand is good insofar as the three

cards in it describe models of volunteer involvement which (a) are realistic, that is,

could very well occur or can be documented as having occurred, and (b) are at the same

time innovative, creative.

Players briefly describe and document their hands for a few

minutes, and then are rated on a scale of I (poorest) to 5 (best) on each of the two

characteristics. Thus a hand can be worth anywhere from two to ten points, unless anyone

gets caught with both pole cards for the same dimension in a given hand. The penalty for

this is extreme. Please note: In describing a hand, a player is restricted as to

involvement style only by the three cards in the hand. On all other seven dimensions, the

player can assume either pole as part of the involvement style described, or can ignore

the other dimension entirely. For example, if neither OCCASIONAL nor CONTINUOUS cards are

in your hand, you can assume the involvement style is either occasional or continuous, or

you can assume this time-extension makes no essential difference in the involvement style.

The above feature of the game, plus the interpretation of the three cards in a hand,

permits considerable scope for creativity and imagination in interpreting a hand to other

players, for purposes of achieving the highest possible score.

7. Who judges or rates the hands? The judges might be a

consensus of all other players, the player to your right on one round and to your left on

the next round. You might also have an outside judge, someone who is knowledgeable,

intelligent, of unimpeachable integrity, and already unpopular with the group. Perhaps

someday there will be fixed ratings for all possible hands in "three-card

style." In any case, this game would be fun and instructive at the same time,

whenever volunteer leaders get together - at workshops and conferences, for example.

I will leave to help-intending cardsharks the further

development of the game, but I can't help speculating. Suppose we are only playing

three-card style. You are dealt:

| Occassional |

|

Informal |

|

Policy |

A creative and feasible combination, this

could be the volunteer who is not on your advisory Board, but whom you call for valuable

advice every now and then - or who calls you (free-lance?) to volunteer his advice (are

you impatient or do you listen?).

The first three cards you draw to try to improve your hand

are:

As Individual |

| |

Work |

| |

For Others |

They don't seem to add much, but the next

card you draw is:

Now that card is interesting. Since I'm

kitbitzing your hand, I suggest you pick up OBSERVER and discard OCCASIONAL. What you then

have could be an informal network of volunteers, targeted to observe certain things

relevant to policy so when you call (or when they call), they will be able to back advice

with evidence. If you described your hand that way, I would give you a rating of 8.

For the next game, you might want more challenge. If so, I

suggest four-card style and after that, five-card style. In this way, we can play our way

through all of volunteer space somewhat before the end of the present century. By that

time we will have succeeded in redefining volunteer space in more precise yet richer

terms. So we can begin the game again.

A final word about redefining volunteer space - the cards

with which our game is played. The worst thing this book could do would be to fixate

either you or me on "the ten dimensions." The best thing this book could do

would be to stir up a dialogue which would unfix the ten dimensions, refine them,

rationalize, and extend them.

I've gone about as far as I can go with the dimensions at

this point, except for some uneasy speculation on how they might be improved. I've already

mentioned overlap between some of the dimensions, and their sometimes logically absurd

combinations, and the new space poles on the right of some dimensions are in need of

rethinking and possibly renaming. For example, is "break-even" the proper end of

the volunteer line from money-losing on that dimension? Or is the pole a bit less or more

than break-even? Is self-help a bit too much to be included in volunteering, and if so,

where is the polar alternative to "for others" best placed? Self-interest?

Reasonable self-interest? Self-interest which doesn't damage the quality of help-intending

work?

Finally, there are certainly other meaningful dimensions

and refinements or realignments of the present dimensions. Some of these are at least

implied by this book's analyses. For example, continuous to occasional appears to involve

at least two other dimensions: time-extensive to time-limited, and regular to irregular.

Lurking somewhere in the irregular area, and in informal volunteering as well, may be

something called "spontaneous" as contrasted with stimulated volunteering (?).

Second, within indirect forms of volunteering, we glimpse a complexity which might

alternately justify two distinct dimensions: working directly with the client or on a

problem or not doing so, and geographical distance from the work site, "electronic

volunteering" being one instance of the latter. (The two are not quite the same

thing; you can work directly with a client by telephone; that is indirectly.) A third

example: the observational pole of action-to-observing might justify within itself a

distinction between sensing and studying, between observation and cogitation. Also, there

is a meaningful difference between volunteering to observe, and volunteering to be

observed. The latter category includes people who volunteer (unpaid) as subjects in a

research study, and it suggests the possibility of an active-to-passive dimension in

styles of volunteer involvement.

Other "new" dimensions might be: helpful to

indifferent to hurtful, and seriousness of work to triviality of work. Both dimensions are

quite subjective, which is why I have avoided them, and both dimensions exit from

volunteer space well before the pole on the right is reached.

I leave all such remapping to you in the confident

expectation of new insights.

- Partial exception: you can integrate work with gift-giving

at the same time (Chapter 13), though it would seem difficult to combine extreme emphasis

on both in the same work. Nevertheless, I do think this is one exception.

- Simple mercy prevented including such a printout as an

appendix to this book – simple mercy and an aesthetic feeling that an appendix should

not be longer than the book itself.

|